Managing Protocol Deviations: GCP Compliance Strategies

Protocol deviations are any departures from an approved clinical trial protocol, whether intentional or unintentional. These deviations, if left unaddressed, directly compromise data integrity, participant safety, and regulatory compliance. While some deviations may appear minor—like a missed visit window—they can quickly escalate if repeated or poorly documented. GCP guidelines require that deviations be captured, analyzed, and mitigated to prevent recurrence and ensure subject protection.

For sponsors, clinical research associates (CRAs), and site coordinators, managing deviations isn’t just a formality—it’s a critical component of inspection readiness and study reliability. Regulatory authorities like the FDA and EMA increasingly scrutinize how deviations are tracked, categorized, and reported. Failure to properly manage even low-impact deviations can lead to warning letters, data exclusions, or delays in product approval. That’s why proactive deviation management systems and GCP-aligned response strategies are essential at every level of trial execution.

Understanding Protocol Deviations in Clinical Trials

Protocol deviations are not just documentation issues—they’re indicators of deeper process weaknesses. Whether driven by operational gaps or clinical urgency, each deviation has the potential to impact trial integrity and trigger regulatory scrutiny. To manage them effectively, research professionals must first understand how deviations are classified and how regulators interpret their consequences.

Major vs. Minor Deviations: Definitions and Examples

Major deviations are those that significantly impact participant safety, data integrity, or protocol compliance. These include enrolling ineligible subjects, administering incorrect dosages, or omitting key safety assessments. For example, if a participant receives the wrong investigational product or bypasses critical lab work, it’s not just a procedural error—it poses ethical and scientific risks that may invalidate data.

In contrast, minor deviations are procedural lapses with limited impact on subject welfare or study quality. Common examples include scheduling visits outside the allowed window or missing a non-critical lab draw. While individually less concerning, repeated minor deviations can reflect systemic training or oversight issues that warrant attention during monitoring visits or inspections.

Distinguishing between major and minor deviations is essential not just for documentation, but for prioritizing response actions and determining reporting obligations to IRBs and regulatory agencies.

The Regulatory Consequences of Unmanaged Deviations

When protocol deviations are poorly managed or systematically ignored, regulatory authorities escalate their level of oversight. Agencies such as the FDA, EMA, and MHRA view deviation trends as signals of broader compliance failures. Findings in Form 483s or warning letters often cite failure to identify, categorize, or report deviations properly.

Sponsors may face trial delays, data rejection, or mandatory corrective actions. For investigative sites, repeated unmanaged deviations can trigger for-cause audits, impact future trial eligibility, and tarnish institutional reputations. Beyond compliance penalties, unmanaged deviations can undermine the scientific credibility of an entire trial, especially when they affect randomization, blinding, or endpoint collection.

Root Causes of Protocol Deviations

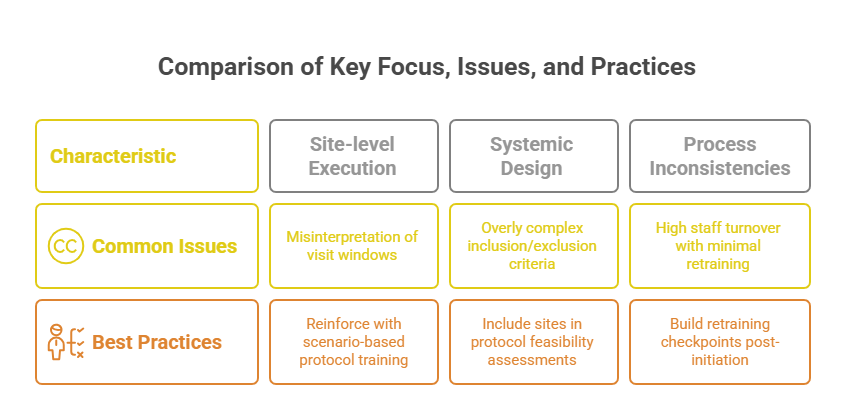

Understanding the underlying causes of protocol deviations is critical to preventing them. These causes typically fall into two categories: site-level issues and systemic design flaws. Addressing both requires cross-functional alignment—from protocol writers to site staff—to build operational feasibility into every aspect of trial conduct.

Site-Level Errors: Training, Misinterpretation, and Oversight

At the site level, staff misinterpretation of protocol requirements is a leading contributor to deviations. Even experienced coordinators can miss procedural nuances, especially in protocols with complex eligibility or visit schedules. Misinterpretations often stem from poorly delivered Site Initiation Visits (SIVs) or inadequate access to clarification tools during the study.

Another frequent issue is incomplete or inconsistent training across site personnel. Sites experiencing high turnover or limited staffing may skip formal handoffs, leading to unauthorized delegation or misexecution of tasks. Oversight gaps by the PI or sub-investigators compound this risk, especially when source data review or CRF completion is rushed under enrollment pressure.

Moreover, deviation trends may emerge from documentation fatigue or electronic system navigation errors, particularly in eCRFs or EDC platforms. When staff struggle to align real-time patient interactions with protocol windows or data entry guidelines, even minor lapses can accumulate into compliance risks.

Systemic Issues: Protocol Complexity and Feasibility Problems

Many deviations originate before a trial even begins—during protocol development. Overly complex protocols that demand tight visit windows, burdensome assessments, or extensive inclusion/exclusion criteria introduce significant risk. When sites are forced to bend rules to retain subjects or meet enrollment targets, deviations become inevitable.

Another systemic driver is poor feasibility planning. Sponsors that fail to evaluate site infrastructure, patient population compatibility, or resource constraints may push unachievable expectations onto research teams. This mismatch often results in protocol non-compliance—not due to negligence, but because the design ignores operational realities.

Additionally, the use of frequent amendments and inconsistent protocol updates across global sites leads to confusion and deviation spikes. Without harmonized communication and ongoing clarification from the sponsor or CRO, even high-performing sites can misapply changes or revert to outdated procedures.

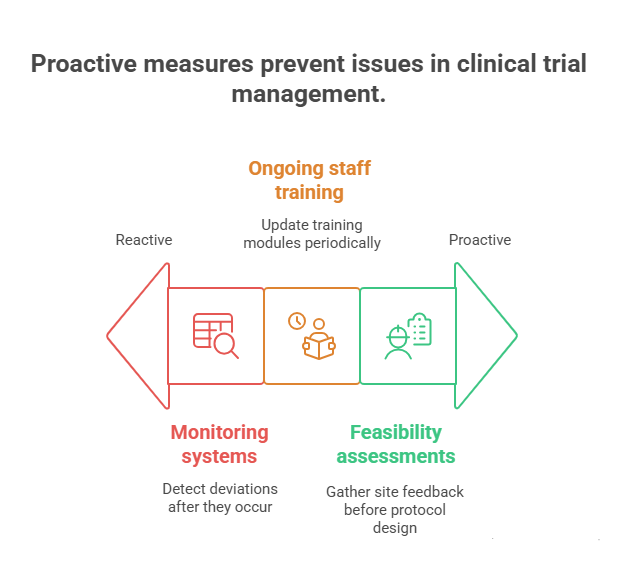

Real-World Strategies to Minimize Deviations

Minimizing protocol deviations requires more than SOPs—it demands front-loaded risk planning, continuous education, and real-time data oversight. The most effective sponsors and CROs don’t react to deviations—they preempt them with proactive systems built into every trial phase.

Pre-Initiation Protocol Review & Feasibility Checks

Before sites are activated, the protocol must undergo a rigorous feasibility assessment, not just for scientific soundness but for operational clarity. This includes checking whether visit windows are realistic, procedures are deliverable within site capacity, and assessments are aligned with local regulatory and logistical constraints.

Top sponsors integrate site feedback into protocol design, especially during investigator meetings and pre-SIV discussions. By mapping out "what could go wrong" in execution, they identify high-risk elements that typically drive deviations—tight screening-to-randomization windows, complicated dosing schedules, or overlapping assessments. Adjustments made at this stage dramatically reduce downstream errors.

Feasibility reviews should also assess site infrastructure. Sites lacking trained staff, patient volume, or EMR compatibility are more likely to cut corners or misinterpret instructions—leading to protocol violations not due to willful negligence, but structural misalignment. Selecting sites based on both capacity and clarity minimizes this risk.

Continuous Investigator and Staff Training

Even well-designed protocols fail when staff don’t internalize critical procedures. One-time investigator meetings are not enough. Sponsors should implement layered training plans that include refresher modules, deviation trend briefings, and scenario-based Q&A throughout the study.

Successful sponsors embed training checkpoints into milestone visits—such as first patient in (FPI), enrollment ramp-up, or protocol amendments. Each checkpoint reinforces critical elements, corrects misinterpretations, and realigns site practices with updated expectations. Sites struggling with deviation patterns should receive targeted retraining on specific procedures or data entry workflows.

Training must be role-specific, interactive, and scenario-driven. Lectures or static slides fail to engage coordinators or new hires. Tools like protocol walkthroughs, deviation simulations, and interactive assessments help teams retain procedural memory under real-world pressure.

Real-Time Monitoring and EDC Alerts

Deviations often occur silently—until audits expose them. Implementing real-time data monitoring systems allows CRAs and data managers to spot red flags early. These include inconsistent dosing records, missing lab entries, or timeline slippages between visits and procedures.

Modern EDC platforms can trigger automated alerts when entries fall outside protocol-specified parameters, allowing for immediate follow-up and correction. Sponsors should customize these alerts based on known high-risk elements—eligibility mismatches, lab value ranges, or dosing intervals—so deviations are caught before they escalate.

GCP and ICH Guidelines on Deviation Documentation

Deviation management isn’t just good practice—it’s a core requirement under ICH-GCP and regulatory law. Proper documentation ensures transparency, enables oversight, and prevents findings during inspections. Yet, many sites still fall short—not in intention, but in execution. This section clarifies the exact expectations and best practices for deviation documentation.

What GCP Requires in Case of Deviations

According to ICH E6(R2), any protocol deviation must be documented, explained, and—if necessary—reported to the sponsor, IRB/IEC, and regulators. Section 4.5.3 and 5.20 emphasize that deviations affecting subject safety or data validity must be acted upon immediately.

Sites are responsible for:

Notifying the sponsor without delay for any significant deviation

Assessing whether the deviation affects patient safety or trial integrity

Initiating Corrective and Preventive Actions (CAPA) where appropriate

Regulators expect not only incident documentation, but a pattern analysis. A single missed ECG may not trigger an alarm—but recurring errors from one coordinator indicate inadequate oversight, which must be addressed proactively.

How to Document & Report: Timing, Format, and Language

Documentation must be contemporaneous, objective, and precise. That means recording the deviation as soon as it's identified—not retroactively at monitoring visits. Every entry should include:

Date of occurrence

Description of the event

Immediate action taken

Assessment of impact (on safety/data)

Root cause

CAPA implementation details

Use neutral, non-defensive language. Avoid subjective terms like “minor error” or vague explanations like “staff oversight.” Instead, state the deviation factually and clarify the outcome. For example: “Subject received investigational product on Day 8 instead of Day 7 due to scheduling error. No safety concerns observed. PI reviewed calendar process and retrained staff.”

Sites should use sponsor-provided templates or Deviation Reporting Forms (DRFs) within the EDC system when available. When manual logs are necessary, these should be kept in the regulatory binder and cross-referenced with monitoring reports and audit trails.

Timeliness matters. For deviations affecting primary endpoints or subject rights, submission to the IRB and sponsor must occur within 24–72 hours, depending on local regulatory standards.

| Documentation Element | ICH GCP Reference | Guideline Summary |

|---|---|---|

| Deviation identification & description | ICH E6(R2) 4.5.1, 5.20.1 | Every deviation must be promptly identified, described in detail, and assessed for safety and data impact. |

| Immediate action taken | ICH E6(R2) 4.5.2 | Sites must document immediate corrective steps taken to protect subject safety and trial integrity. |

| Assessment of impact | ICH E6(R2) 5.20.1 | Sponsors and investigators must determine whether the deviation affects data validity or subject risk. |

| Root cause analysis (RCA) | ICH E6(R2) 5.20.2 | Underlying causes should be identified to prevent recurrence through corrective/preventive actions. |

| Deviation reporting | ICH E6(R2) 4.5.3, 5.20.1 | Deviations that significantly affect rights, safety, or reliability must be reported to the sponsor and IRB/IEC. |

| Document language & tone | GCP Best Practice | Language must be neutral, objective, and free from assumptions or blame. |

| Timeliness of entry | ALCOA-C (FDA, GCP) | Deviation entries must be contemporaneous—recorded as soon as identified, not retroactively. |

Sponsor and Monitor Responsibilities During Audits

When deviations are reviewed during audits or inspections, sponsors and monitors are under direct scrutiny for how well they identified, responded to, and mitigated risks. Regulatory bodies assess not just site compliance—but the sponsor's entire oversight framework. A failure to manage recurring deviations signals systemic weakness, not just isolated mistakes.

Audit Trails and Root Cause Analysis

Auditors will review electronic audit trails and monitoring visit reports to determine how quickly and effectively deviations were detected. EDC platforms must show who entered or modified data, when the change occurred, and why. If this metadata is incomplete or inconsistent, it raises questions about trial integrity and oversight.

CRAs must ensure that every deviation discussed at a visit is documented, followed up, and closed appropriately. Notes to file without corrective action aren’t enough. Sponsors should have systems in place that track deviation trends across sites, allowing them to detect systemic risks before regulators do.

Root cause analysis (RCA) is essential when deviations recur. It's not enough to describe what happened—you must analyze why it happened and what will prevent it in the future. Sponsors should adopt structured RCA tools like the "5 Whys" or fishbone diagrams to identify process, personnel, or design flaws.

Without RCA, CAPAs risk being superficial, and regulators will view them as insufficient.

CAPAs and Long-Term Process Improvements

Corrective and Preventive Actions (CAPAs) must be more than checkboxes. Auditors expect to see evidence of effective CAPA implementation, from updated SOPs and training logs to revised monitoring plans and feasibility criteria.

Sponsors must track whether the same type of deviation resurfaces in future trials or sites. If it does, it signals a failed CAPA. Strong CAPA systems include:

Owner assignment and due dates

Measurable effectiveness checks

Documentation of sustained improvement over time

Monitors also play a pivotal role. During routine visits, they must assess not just individual errors, but deviation patterns and site response behaviors. Sites with persistent issues may require enhanced oversight or even temporary suspension from enrollment.

Long-term process improvement isn’t optional—it’s how sponsors prove that GCP is embedded not just at the site, but across the trial ecosystem.

| Responsibility | Sponsor/Monitor Action | Audit Expectation |

|---|---|---|

| Deviation detection | Use monitoring reports, EDC queries, and site visit observations to identify protocol deviations in real time. | Auditors expect traceable evidence of deviation detection and CRA documentation timelines. |

| Audit trail review | Review EDC metadata to track who made changes, when, and why—especially around deviation entries. | Inspection teams examine audit trails for transparency and timeliness of corrections or entries. |

| Root cause analysis (RCA) | Apply structured RCA tools (e.g., 5 Whys) to analyze deviation trends across sites or time points. | Regulators assess whether RCA was thorough, systemic, and used to inform CAPAs. |

| CAPA implementation | Draft and enforce Corrective and Preventive Actions with clear owners, deadlines, and effectiveness checks. | Audits evaluate CAPA depth, follow-through, and evidence of sustained resolution. |

| Site oversight | Escalate persistent deviation patterns, retrain staff, or pause site enrollment if issues recur. | Inspectors look for proactive intervention and communication logs documenting site performance management. |

How the Good Clinical Practice Certification by CCRPS Equips You for Deviation Management

Clinical research professionals are only as strong as their understanding of regulatory expectations. The Good Clinical Practice Certification by CCRPS is specifically designed to prepare CRAs, CRCs, and site managers to detect, document, and mitigate protocol deviations in line with global regulatory standards.

This certification goes beyond theoretical GCP definitions. It walks learners through real-world deviation scenarios, emphasizing how to classify, report, and follow up in ways that withstand audit scrutiny. You’ll gain deep expertise in distinguishing major vs. minor deviations, structuring deviation reports, and initiating CAPAs that pass FDA, EMA, and ICH inspections.

Mastering Deviation Classification and Documentation

The course dedicates full modules to deviation categorization, impact assessment, and documentation techniques. It doesn’t stop at form filling—it teaches you how to write deviation narratives that are objective, audit-ready, and regulator-friendly. You'll learn:

How to align deviation language with ICH E6(R2)

When to escalate deviations to IRBs and sponsors

What to include in a CAPA response for long-term mitigation

This level of detail ensures learners don’t just meet compliance—they internalize it.

Practical Training in Root Cause Analysis (RCA)

Where most GCP programs skim over RCA, this certification delivers structured RCA training tailored for protocol deviations. You’ll work through:

Deviation case studies that reveal underlying systemic issues

Tools like 5 Whys, Pareto charts, and fishbone diagrams

Guidance on translating RCA insights into sustainable SOP changes

By the end of the course, you won’t just react to deviations—you’ll know how to prevent their recurrence across multiple studies.

CAPA Planning and Inspection Readiness

Inspectors often evaluate how effective a site or sponsor’s CAPAs are. This certification prepares professionals to:

Draft CAPA plans that are timeline-driven and outcome-focused

Track deviation trends using logs, EDC metadata, and audit reports

Build evidence of improvement that withstands regulatory review

The course also trains you to handle deviation discussions during inspections, whether you’re a monitor, coordinator, or sponsor representative. You’ll know how to respond confidently, reference the protocol correctly, and point to preventive actions already underway.

Whether you're working at a site, CRO, or sponsor organization, the Good Clinical Practice Certification by CCRPS equips you with the tools to protect subject safety, preserve data validity, and maintain regulatory credibility.

Frequently Asked Questions

-

A protocol deviation occurs when the actual conduct of a clinical trial diverges from the approved protocol, informed consent process, or regulatory requirements. These deviations may be intentional or unintentional and range from missing a lab visit to administering incorrect dosages. ICH-GCP guidelines require that all deviations be documented, assessed for impact, and—if significant—reported to sponsors or IRBs. What qualifies as a deviation depends on whether the action compromises participant safety, data integrity, or trial compliance. Even small procedural errors become critical if repeated or affecting primary endpoints. Every deviation should be logged with a description, date, corrective action, and root cause.

-

Major deviations affect subject safety, trial validity, or regulatory compliance—such as dosing errors, unauthorized changes to treatment regimens, or enrolling ineligible participants. These typically require immediate sponsor notification and IRB reporting. Minor deviations include procedural lapses like visit window violations or delayed data entries that do not compromise safety or endpoint integrity. Regulatory authorities expect sponsors and monitors to categorize deviations correctly based on risk, recurrence, and consequence. Importantly, repeated minor deviations can escalate into major concerns if they reflect systemic issues. Always assess impact and document both the deviation and the rationale behind its classification.

-

Not all deviations require IRB or regulatory reporting. Significant deviations—those affecting subject safety, rights, or trial integrity—must be reported promptly, often within 24–72 hours. These include dosing misadministration, safety data omissions, or violations of eligibility criteria. However, minor, low-impact deviations may only need to be documented internally and tracked by the sponsor. Each IRB may have its own reporting thresholds, so familiarity with their specific guidance is crucial. Sponsors typically define in their SOPs which deviations are reportable. Still, the general rule is: if the deviation introduces risk or affects key endpoints, it must be reported.

-

Documentation must be contemporaneous, factual, and complete. Each deviation log entry should include the date of occurrence, a detailed but objective description, the assessed impact, immediate corrective actions, root cause analysis, and any preventive steps implemented. Use Deviation Report Forms or EDC-integrated logs whenever available. Avoid subjective language like "minor issue" or vague phrases such as "staff oversight." Instead, state specific facts—for example, “Subject missed Visit 3 due to scheduling conflict. Safety assessments completed at Visit 4. No data lost.” Proper documentation helps with audit readiness, trend analysis, and regulatory credibility.

-

Corrective and Preventive Action (CAPA) plans are essential for resolving protocol deviations and preventing recurrence. A CAPA should identify the root cause, define specific corrective steps (e.g., retraining staff, updating SOPs), assign responsible personnel, and set timelines for implementation. CAPAs are auditable documents—regulators often assess them during inspections to judge whether the sponsor or site took deviations seriously. Effective CAPA systems also include effectiveness checks, where follow-up reviews confirm that the issue has not re-emerged. A CAPA that fails to prevent similar future deviations may result in regulatory findings or escalated oversight.

-

Yes. Accumulated or serious deviations can trigger regulatory audits, data reviews, or IRB holds, all of which cause delays. Deviations that compromise endpoint collection, violate randomization schedules, or raise safety concerns may require data exclusion, reanalysis, or corrective rescreening. In multicenter trials, unresolved deviations at one site can affect the entire trial’s data pool. Sponsors may also pause enrollment at underperforming sites or increase monitoring frequency, consuming time and resources. Regulatory bodies may require additional documentation or impose corrective mandates before the study can proceed. Preventing deviations through proactive oversight saves both time and credibility.

-

Effective training ensures that site staff understand and correctly execute every protocol procedure. Ongoing, scenario-based training reinforces key instructions beyond the Site Initiation Visit. It reduces the likelihood of errors due to misinterpretation, forgotten steps, or procedural drift. High-deviation sites often suffer from inconsistent onboarding, role ambiguity, or protocol fatigue. Training should be role-specific (e.g., dosing for nurses, data entry for CRCs) and adapt to protocol amendments. It’s not just about delivering materials but confirming comprehension through assessments and simulations. Well-trained teams are quicker to flag uncertainties, reducing both the frequency and severity of deviations.

Final Thoughts

Protocol deviations are more than administrative mishaps—they are compliance risks that jeopardize subject safety, data reliability, and regulatory approval. Sponsors, CRAs, and site staff must embed deviation management into every phase of the trial, from feasibility and training to monitoring and audit preparation.

By applying GCP-aligned strategies, conducting real-time deviation tracking, and enforcing CAPA frameworks backed by root cause analysis, organizations can drastically reduce error frequency. Proactive handling not only prevents inspection findings—it also ensures ethical conduct and scientific credibility.

For professionals seeking mastery in this area, the Good Clinical Practice Certification by CCRPS offers targeted, tactical training that directly translates to better deviation oversight. In a regulatory climate where every deviation is a potential audit trigger, prevention is not optional—it’s essential.